The Strategic Reconfiguration of the Horn of Africa: Israel, Somaliland, and the 2025 Regional Realignment

The formal recognition of the Republic of Somaliland by the State of Israel on December 26, 2025, represents a transformative moment in the geopolitical architecture of the Horn of Africa and the broader Red Sea basin.1 This diplomatic maneuver, the first of its kind by a United Nations member state, has acted as a catalyst for a complex array of strategic, economic, and security-driven realignments involving the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Ethiopia, and the United States.1 At the heart of this transformation lies a convergence of interests: Israel’s requirement for strategic depth against Iranian-backed proxies, the UAE’s ambition to consolidate control over maritime trade corridors, and Somaliland’s three-decade quest for sovereign legitimacy.4 This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the historical, theological, and tactical factors driving this realignment, the secret military infrastructures in place, and the broader global contest for control over the world’s most critical maritime chokepoints.

The Historical Genesis of a Fragmented Sovereignty

The modern crisis in the Horn of Africa cannot be understood without a deep historical examination of the 1960 unification and its subsequent collapse. Modern Somalia emerged from the merger of two distinct colonial entities: the British Somaliland Protectorate in the north and Italian Somaliland in the south.6 The British protectorate, established through treaties with various Somali chiefs in 1886, was primarily a strategic asset designed to safeguard trade links to the East and secure local food supplies for the coaling station in Aden.6 When the State of Somaliland gained independence from the United Kingdom on June 26, 1960, it existed as a sovereign nation for five days before voluntarily uniting with the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian colony) on July 1, 1960, to form the Somali Republic.6

This union was structurally flawed from its inception, as it attempted to merge two entities with divergent legal systems, administrative traditions, and languages of governance.7 The initial parliamentary democracy (1960–1969) was characterized by clan-based tensions that ultimately led to the 1969 coup d’état by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre.7 Barre’s “Scientific Socialism” regime, while initially promising national unity, eventually devolved into a brutal military dictatorship that favored his own sub-clans while marginalizing northern groups, particularly the Isaaq clan.8

The eventual collapse of the central state in 1991 followed years of civil war, leading northern leaders to withdraw from the 1960 union and declare the independent Republic of Somaliland on May 18, 1991.6 Since that time, Somaliland has developed all the attributes of a sovereign state—including its own currency, passport, military, and a series of democratic elections—yet it remained in a state of diplomatic isolation for over thirty years.3

| Key Eras in Somali Political History | Period | Defining Characteristics |

| Pre-Colonial Sultanates | Pre-1880s | Domain of the Adal Sultanate and various clan-based maritime trade networks.9 |

| Colonial Protectorates | 1884–1960 | Division between British (North) and Italian (South) administration.6 |

| Independence and Union | 1960–1969 | Short-lived parliamentary democracy following the 1960 merger.7 |

| Siad Barre Dictatorship | 1969–1991 | Military rule, Cold War maneuvering, and eventually civil war.7 |

| Collapse and Secession | 1991–2025 | Unilateral declaration of independence by Somaliland; fragmentation in the south.3 |

| Recognition Era | Post-Dec 2025 | Israel becomes the first UN member to recognize Somaliland sovereignty.1 |

The Israeli Strategic Calculus: Recognition as the “Periphery Doctrine” 2.0

Israel’s decision to recognize Somaliland in December 2025 was the culmination of an extensive and ongoing dialogue conducted through the Mossad.2 Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar signed the declaration following a high-level virtual meeting with Somaliland President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi.2 The rationale for this move is primarily geopolitical rather than ideological, rooted in Israel’s “Periphery Doctrine”—a historical strategy of building alliances with non-Arab or non-hostile states on the edges of the Arab world to break encirclement.15

The immediate driver for recognition is the threat posed by the Houthi movement in Yemen and its sponsor, Iran. By establishing a formal presence in Somaliland, Israel gains a strategic foothold overlooking the Gulf of Aden and the Bab al-Mandab Strait.1 This location is vital for monitoring Houthi activities and thwarting drone or missile attacks on commercial vessels transiting toward the Israeli port of Eilat.1 Somaliland’s Berbera port and modernized airstrip provide the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) with a platform for intelligence collection, logistical support for naval patrols, and potential offensive strikes against Houthi military targets.4

The Secret Dimensions: Palestinian Relocation and Intelligence Networks

A controversial “secret” that emerged in the wake of recognition involves allegations regarding the forced displacement of Palestinians. Multiple sources, including Chinese intelligence and the Palestinian Authority, have characterized Israeli recognition as a prelude to a plan to resettle Palestinians from the Gaza Strip into Somaliland.1 These reports suggest that Somaliland was identified as a destination for Gazans as part of a broader strategy to alter the demographic reality of the Palestinian territories.1 While the Somaliland government has been cautious in its public responses, analysts note that Hargeisa’s desperation for recognition may have made them susceptible to such proposals, even though they remain highly unpopular among the local population.18

Furthermore, the intelligence cooperation between Israel, the UAE, and Somaliland is coordinated through the “Crystal Ball” platform. This network allows for real-time sharing of data collected from Israeli-made radar systems and other surveillance apparatuses deployed across the Somali coast. The objective is to create an integrated air and missile defense umbrella that protects the commercial and military interests of the UAE-Israel axis from Iranian-backed asymmetric threats.20

The UAE’s Role: Ports, Logistics, and the Sudan War Hub

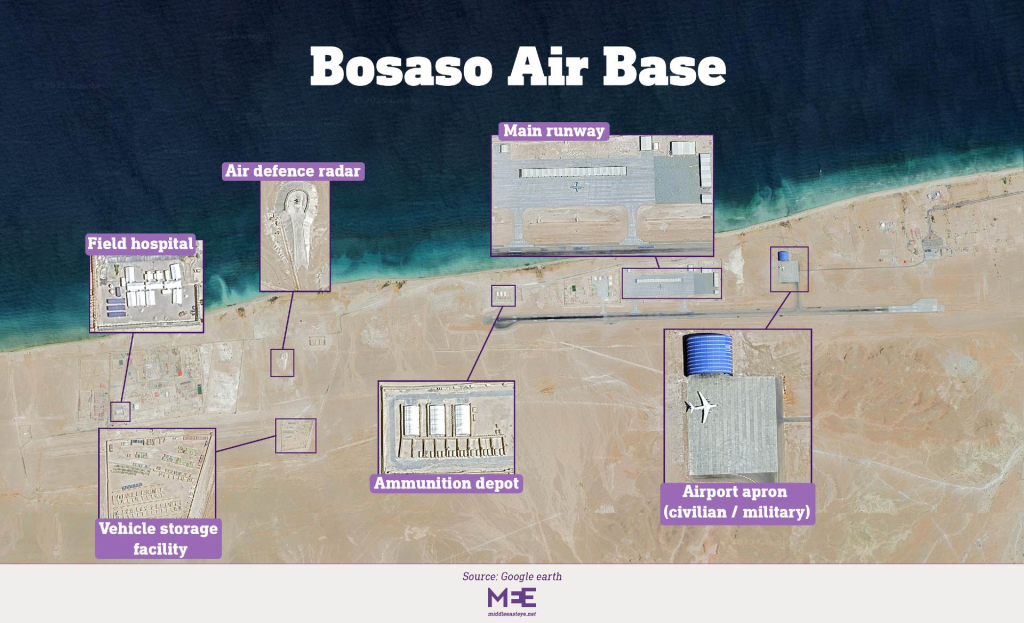

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has acted as the primary architect of the covert military and logistics infrastructure that now spans northern Somalia. Since 2018, the UAE has maintained a military base in Berbera, which includes a naval port and an airstrip for fighter jets and transport aircraft.22 However, the most significant developments in 2024 and 2025 have centered on Bosaso, the commercial hub of the Puntland state.24

Investigations by Middle East Eye and Brown Land News revealed that Bosaso Airport has been transformed into a secret logistical hub for the UAE’s support of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan’s ongoing civil war.22 Since 2023, IL-76 cargo transports operated by Emirati-owned shell companies, such as Gewan Airways, have frequently landed in Bosaso during periods of minimal activity.22 These planes carry “hazardous” materials and military logistics that are swiftly transferred to outbound aircraft bound for RSF-controlled areas in Sudan via Chad or Libya.25

Military Presence: Mercenaries and Advanced Technology

The presence of foreign military elements in Bosaso and Berbera is no longer a matter of speculation. Reports from 2025 confirmed that the UAE has deployed Colombian mercenaries, recruited by the Global Security Service Group (GSSG), through Bosaso.22 These paramilitaries are processed at a fortified camp north of the airport before being flown to Darfur to fight alongside the RSF.22

| Secret Military Infrastructure | Location | Key Function |

| IL-76 Airlift Bridge | Bosaso Airport | Direct supply line for RSF military equipment.22 |

| ELM-2084 3D Radar | Bosaso Base | Israeli-made system for missile and drone defense.24 |

| Colombian Mercenary Camp | Bosaso | Training and transit hub for GSSG recruits bound for Sudan.22 |

| Hazardous Cargo Port | Bosaso Port | Transit of over 500,000 undocumented containers for RSF supply.25 |

| Dual-Use Naval Facility | Berbera Port | Staging ground for UAE-Israeli maritime patrols in the Gulf of Aden.4 |

Additionally, Israel has supplied advanced technology to secure these UAE-run facilities. Early in 2025, an Israeli-made ELM-2084 3D Active Electronically Scanned Array radar was installed near Bosaso airport to protect the hub from Houthi retaliation.24 This highlights a three-way entanglement: Somaliland and Puntland provide the geography, the UAE provides the financing and logistics, and Israel provides the security and technological superiority.1

Ethiopia’s Maritime Quest: The 2024 MoU and Strategic Silence

Ethiopia’s involvement in the Somaliland realignment is driven by an existential imperative for maritime access. As a landlocked nation of $120$ million people, Ethiopia currently relies on Djibouti for $95\%$ of its international trade, which Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has identified as a critical national security vulnerability.29 On January 1, 2024, Ethiopia signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Somaliland that would grant Ethiopia 50-year access to a $20$-kilometer strip of coastline near Berbera for the development of a naval port.29 In exchange, Ethiopia pledged to be the first African country to formally recognize Somaliland.30

The reaction from the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) was a diplomatic “political storm,” leading to the expulsion of the Ethiopian ambassador and the signing of a defense pact between Somalia and Turkey.31 However, Ethiopia has remained relatively quiet since early 2025, pursuing a “strategic recalibration”.29 The benefit for Ethiopia in this silence is twofold. First, the Ankara Declaration of December 2024, mediated by Turkey, provided a pathway for Ethiopia to negotiate sea access through Mogadishu while maintaining its de facto ties with Hargeisa.29 Second, Israel’s subsequent recognition of Somaliland has provided Ethiopia with a powerful international ally that validates Hargeisa’s sovereignty, reducing the pressure on Addis Ababa to be the sole “rogue” state flouting the African Union’s consensus on borders.4

Ethiopia views the 2025 Israel-Somaliland deal as a “Hegelian synthesis” that moves beyond the initial confrontation toward a more sustainable, negotiated pathway where Ethiopia can eventually secure multiple ports—Berbera, Zeila, and potentially sites in southern Somalia—under a broader regional security umbrella.29

The “Ibrahim Accord”: Theological Branding and Political Normalization

The “Ibrahim Accord” mentioned in the query refers to the Abraham Accords, a series of bilateral normalization agreements brokered by the United States between Israel and several Arab and Muslim states, including the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan.20 The name “Abraham” was chosen to emphasize the shared monotheistic roots of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, utilizing the figure of the common patriarch to foster a culture of coexistence.20

Muslim countries justify their participation in these accords through a combination of pragmatic realpolitik and alternative religious discourse.34 The UAE, for instance, has championed “Abrahamic discourse” to counter radical Islamist narratives and promote religious tolerance as a foundation for economic prosperity.34 In Morocco’s case, normalization was exchanged for US recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.32 For Sudan, the incentive was the removal from the US State Sponsors of Terrorism list and access to $1.2$ billion dollars in World Bank loans.20

Somaliland has explicitly expressed its intention to accede to the Abraham Accords following Israel’s recognition, viewing the framework as a “step toward regional and global peace”.3 By joining the accords, Somaliland hopes to institutionalize its relationship with Israel and the UAE while bypassing the ideological barriers that have historically kept African Muslim nations from engaging with the Jewish state.12

| Abraham Accords Component | Primary Objective | Applied Logic in Somaliland Case |

| Diplomatic Normalization | Full exchange of embassies. | Formalization of the Dec 2025 declaration.2 |

| Security Cooperation | Integrated defense against Iran. | Deployment of Israeli radar and maritime patrols.20 |

| Economic Integration | Technology and trade synergies. | Cooperation in agriculture, water, and digital tech.4 |

| Religious Tolerance | “Abrahamic” cultural exchange. | Countering the narrative of Somalia as a purely “anti-Zionist” state.34 |

The Border Crisis: Sool, Sanaag, and the Dhulbahante Rebellion

A critical challenge to the legitimacy of the “Republic of Somaliland” is the contested status of its eastern borders, specifically the regions of Sool, Sanaag, and Cayn (SSC).41 Somaliland claims these areas based on the colonial boundaries of the former British protectorate.41 However, the Dhulbahante clan, which inhabits these regions, has long rejected Isaaq-dominated rule from Hargeisa, preferring to be part of a unified Somalia or a separate federal member state.41

In December 2022, a mass protest in the town of Las Anod escalated into a full-scale armed conflict between the Somaliland army and local Dhulbahante militias.3 By August 2023, the Somaliland army was routed at the battle of Goojacade, forcing a retreat toward the Oog area.43 The Dhulbahante elders then declared the establishment of the SSC-Khatumo state, which was officially recognized by the Federal Government of Somalia in April 2025 and later renamed the “North Eastern State of Somalia” in July 2025.44

As of late 2025, the map of Somaliland’s borders shows that Hargeisa no longer exerts de facto control over the majority of the Sool and Sanaag regions.42 A militarized frontline exists approximately $170$ km from Las Anod, between the villages of Oog and Guumays.44 This internal fragmentation complicates the international community’s ability to recognize Somaliland, as it cannot demonstrate effective territorial control over the borders it claims.41

| Contested Region | Claiming Entities | 2025 Status of Control |

| Las Anod (Sool) | Somaliland / North Eastern State | Under the control of Dhulbahante/SSC-Khatumo forces.43 |

| Ceerigaabo (Sanaag) | Somaliland / North Eastern State | Divided; checkpoints manned by rival sub-clan militias.42 |

| Buuhoodle (Cayn) | Somaliland / North Eastern State | Highly militarized; center of unionist Dhulbahante activity.41 |

| Oog Frontline | Somaliland | The current limit of Hargeisa’s eastward administrative reach.44 |

America’s Paradox: Pentagon Interests vs. State Department Integrity

The United States’ position on Somaliland is characterized by a significant internal divide between the Department of State and the Department of Defense (Pentagon). For decades, the State Department has adhered to a “One Somalia” policy, fearing that recognizing Somaliland would encourage secessionist movements across Africa and undermine the fight against Al-Shabaab in southern Somalia.18 Washington provides significant military assistance to the Somali National Army and operates drone bases in the south to target Al-Qaeda and ISIS affiliates.18

However, the Pentagon and influential Republican members of Congress—including Senator Ted Cruz—have increasingly viewed Somaliland as a “strategic asset”.13 They argue that the Berbera port offers a stable alternative to Djibouti, where Chinese influence is growing and the US military presence is “deteriorating”.13 Legislation such as the “Somaliland Partnership Act” and the “Republic of Somaliland Independence Act” has been introduced to force the State Department to establish a formal representative office in Hargeisa.46

The Trump Administration’s Role in 2025

The return of Donald Trump to the presidency in 2025 has accelerated this debate. While Trump has publicly expressed skepticism about recognizing Somaliland—famously asking “Does anyone know what Somaliland is, really?”—his administration’s “Project 2025” and individual advisers like Michael Rubin have advocated for recognition as a “hedge” against China.3 Netanyahu has reportedly pledged to “make Trump understand” the benefits of recognition, linking it directly to the success of the Abraham Accords and the containment of Iranian influence in the Red Sea.4

The US allows these developments primarily because they align with broader objectives of maritime security and the containment of China, even if they violate the formal commitment to Somalia’s territorial integrity.20 The US military has already conducted high-level visits to Berbera, signaling that de facto cooperation will continue regardless of de jure recognition status.23

The Global Flashpoints: Bab al-Mandab, Red Sea, and Black Sea

The strategic significance of the Horn of Africa is rooted in its proximity to the Bab al-Mandab Strait, the “southern gate” of the Red Sea.49 This strait is a global chokepoint through which up to a quarter of the world’s shipping passes annually.50 Control of this waterway grants a nation the power to influence the global economy, as evidenced by the $55\%$ reduction in maritime traffic following Houthi attacks in 2024–2025.51

Who Can Access?

Access to these waters is currently a matter of contested military dominance. The United States and its allies operate through a “multinational task force” (CMF) to ensure freedom of navigation.50 China maintains a permanent base in Djibouti to protect its “Maritime Silk Road” and its energy supplies from the Gulf.1 Russia, meanwhile, has signaled its intent to establish a naval base in Sudan to project power into the Indian Ocean and bypass Western sanctions.52

| Maritime Chokepoint | Strategic Role | Current Contestation |

| Bab al-Mandab | Southern entrance to the Red Sea. | Site of Houthi asymmetric warfare and US/EU naval reaction.49 |

| Turkish Straits | Connection between Black Sea and Mediterranean. | Controlled by Turkey under the Montreux Convention; flashpoint for Russia-Ukraine conflict.55 |

| Suez Canal | Northern exit of the Red Sea to Europe. | Vulnerable to blockage (Ever Given) and economic contagion from southern attacks.53 |

| Strait of Hormuz | Mouth of the Persian Gulf. | Primary artery for global oil; subject to Iranian closure threats.53 |

Why China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia Oppose Israel

China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia share a common opposition to Israeli presence in the Red Sea, albeit for different reasons. China views Israeli recognition of Somaliland as a tool of “Western hegemony” that destabilizes the region and threatens Chinese infrastructure investments.1 Russia views the Red Sea as a “second front” in its war with the West; by supporting Houthi attacks on Israeli-linked shipping, Moscow can drain Western military resources and keep oil prices high, which benefits the Russian economy.52

Saudi Arabia, despite its own rivalry with Iran, fears that Israeli recognition of Somaliland will “inflame tensions” and turn the Red Sea into a “powder keg” of direct kinetic conflict.2 Riyadh prefers a regional security architecture led by the Council of Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Littoral States, which excludes Israel.15

Scenario Analysis: Houthi Attacks on Somaliland

If the Houthi rebels in Yemen were to follow through on their threat to attack Somaliland, the consequences would be catastrophic for regional stability.58 Abdulmalik al-Houthi has stated that any Israeli presence in Somaliland will be a “military target”.58

A Houthi strike on Berbera or Bosaso would likely involve advanced drones or medium-range ballistic missiles supplied by Iran.56 Such an attack would not only destroy critical infrastructure but could also trigger a massive regional war. Israel would likely respond with long-range air strikes from its F-35 fleet, while the UAE and potentially the US could be drawn into defensive operations.4 Furthermore, an attack on Somaliland would incentivize Hargeisa to deepen its military alliance with Israel, potentially leading to the permanent basing of IDF special forces and interceptor systems on African soil.4

The economic fallout would include the total closure of the Berbera port for commercial traffic, devastating the economies of both Somaliland and landlocked Ethiopia.17 This risk of “geopolitical contagion” is why many regional powers, including Egypt and Saudi Arabia, have so strongly condemned Israel’s recognition.14

Undersea Infrastructure: The Digital Chokepoints

The conflict in the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa also threatens the “invisible arteries” of the global internet—undersea cables.62 The Middle East and East Africa serve as critical transit zones linking Europe and Asia, with a dense cluster of cables passing through the narrow waters of the Bab al-Mandab.62

In 2024 and 2025, major systems such as SEA-ME-WE 4 and SEACOM suffered outages attributed to maritime activity and potential sabotage.62 High-density corridors face weekly disruptions, and the International Cable Protection Committee reported up to 200 outages in 2025 alone.62 The militarization of Somaliland and the potential for Houthi retaliation significantly elevate the systemic risk to global communications. If a conflict were to sever these cables, the economic degradation in India, the UAE, and the broader Middle East would be profound.62

| Undersea Cable System | Reach | Vulnerability Status |

| AAE-1 / EIG | Asia to Europe via Red Sea. | Severed in 2024/2025 during Red Sea crisis.62 |

| BCS East West | Baltic Sea corridor. | Hotspot for Russian-Western hybrid warfare sabotage.62 |

| EstLink 2 | Gulf of Finland. | Damaged in 2024 by maritime anchors; demonstrates accidental/hybrid risk.62 |

Conclusion: The New Regional Order

The recognition of Somaliland by Israel in late 2025 has finalized the transition of the Horn of Africa from a peripheral zone of instability to a central theater of global power competition. The secret deals between Hargeisa, Jerusalem, and Abu Dhabi have established a military and logistical backbone that sustains the UAE’s regional proxy wars while providing Israel with a forward platform against Iran.4

However, this “Somaliland Model” of strategic recognition carries profound risks. It has deepened the internal fragmentation of Somalia, emboldened unionist rebellions in Sool and Sanaag, and provided the Houthis with a new target in their campaign against the West.14 For Ethiopia, the recognition offers a pathway to the sea, but one that is fraught with the potential for direct military entanglement in the Arab-Israeli conflict.17

As the Trump administration evaluates its stance in 2025, the debate in Washington will center on whether the benefits of a “permanent counterweight to Iranian influence” in Berbera outweigh the risks of a broader regional war.5 The Horn of Africa is no longer just a “Land of Punt” or a fragmented former colony; it is the strategic node upon which the future of Red Sea security and global maritime trade will be decided

Leave a comment